Quick reminder about how the bond market works

Genevieve Signoret

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

Every so often we review for our investors why bond yields and prices move in opposite directions.

We saw this week that yields on U.S. Treasuries kept moving up after the March 16 announcement that the Fed would be starting to tighten its monetary policy stance. Here again is that chart showing the bond market response:

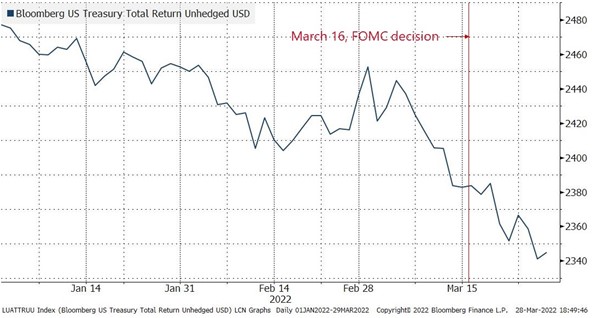

Yields on U.S. Treasury securities have stayed on their upward trend

Chart 1. U.S. Treasury yield curve March 28, March 15, and at the end of last year (% per annum)

What confuses many people is the following: an upward shifting yield curve can also be depicted by a downward sloping bond price curve.

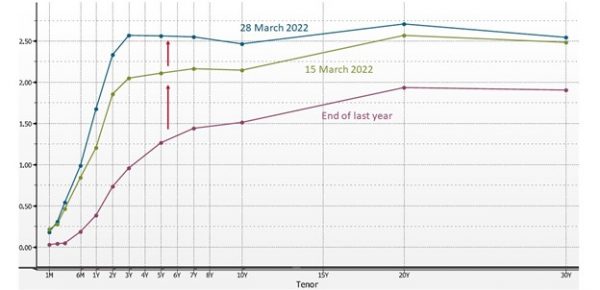

U.S. Treasury securities stayed on their downward price trend (yields kept moving up)

Chart 2. Bloomberg U.S. Treasury Total Return index, year to 28 March 2022

To understand bond markets at all, it’s crucial that you understand why these upward movements in bond yields and downward movements in bond prices are equivalent. So here goes:

Once rates have risen, the coupon paid by a bond trading on the secondary market (that is, one that was originally issued in the past, when rates were lower) will now pay a coupon rate too low to be able to attract buyers. So demand and supply forces will drive the price of that bond down till it pushes the effective yield on the bond (which considers not only coupon payments but also the bond purchase price) to the new, higher prevailing rate.

Numerical example: If you saw a $100 bond that was due in one year and paid a single 5% coupon at the end of the year when the prevailing market rate was 5.2%, would you pay $100 for it? Nope. You’d demand a discount. How much of a discount? One that results in your earning the prevailing market rate of 5.2%, which $3.85. (A single $5 coupon paid one year from now on a bond you purchased today at $96.15 would deliver you the 5.2% rate of return would need to tempt you into this purchase).

What this numerical example has just demonstrated is that, for the bond market to clear, bond prices must immediately adjust down when interest rates move up.

The opposite is true also, by the way. When rates fall, bonds trading on the secondary market start to trade at higher valuations. The arithmetic works exactly the same but in the opposite direction: instead of trading at a discount, the price of a $100 bond will start to trade at a premium.